- Ariel LeBeau

- Austin Robey

- David Blumenstein

- David Ehrlichman

- David Kerr

- Devon Moore

- Dexter Tortoriello

- Drew Coffman

- Drew Millard

- Eileen Isagon Skyers

- FWB Staff

- Greg Bresnitz

- Greta Rainbow

- Ian Rogers

- Jessica Klein

- Jose Mejia

- Kelani Nichole

- Kelsie Nabben

- Kevin Munger

- Khalila Douze

- Kinjal Shah

- LUKSO

- Lindsay Howard

- Maelstrom

- Marc Moglen

- Marvin Lin

- Mary Carreon

- Matt Newberg

- Mike Pearl

- Mike Sunda (PUSH)

- Moyosore Briggs

- Nicole Froio

- Ruby Justice Thelot

- Simon Hudson

- Steph Alinsug

- The Blockchain Socialist

- Willa Köerner

- Yana Sosnovskaya

- Yancey Strickler

- iz

Thu Jan 12 2023

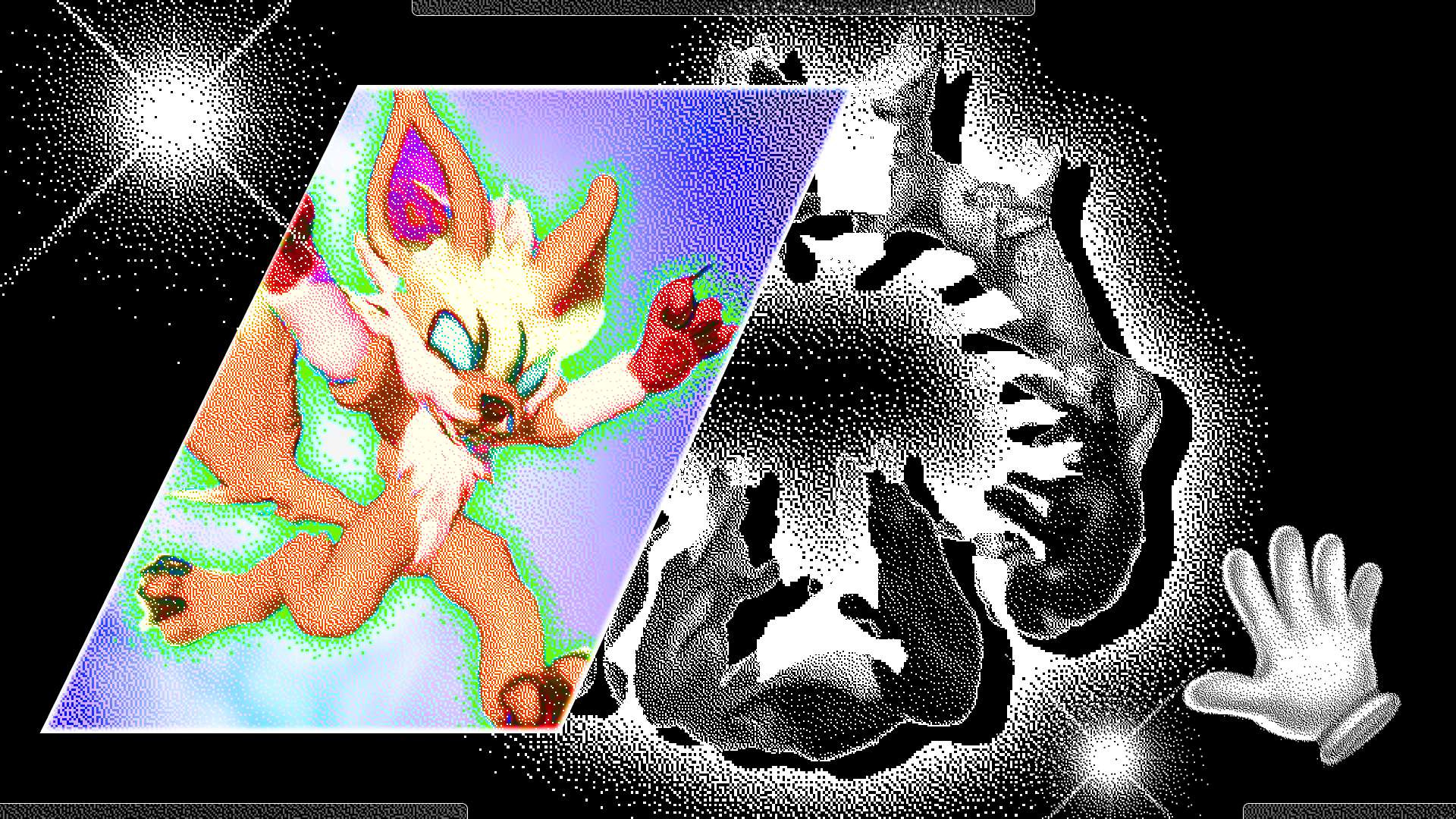

In November 2021, VincentVanDough, a self-described “purveyor of shitcoins and fine art,” announced that he had a new artwork for sale. “This piece is dedicated to the furries,” read the description on NFT marketplaces. “They may not understand the value of provenance yet, but they will soon enough.”

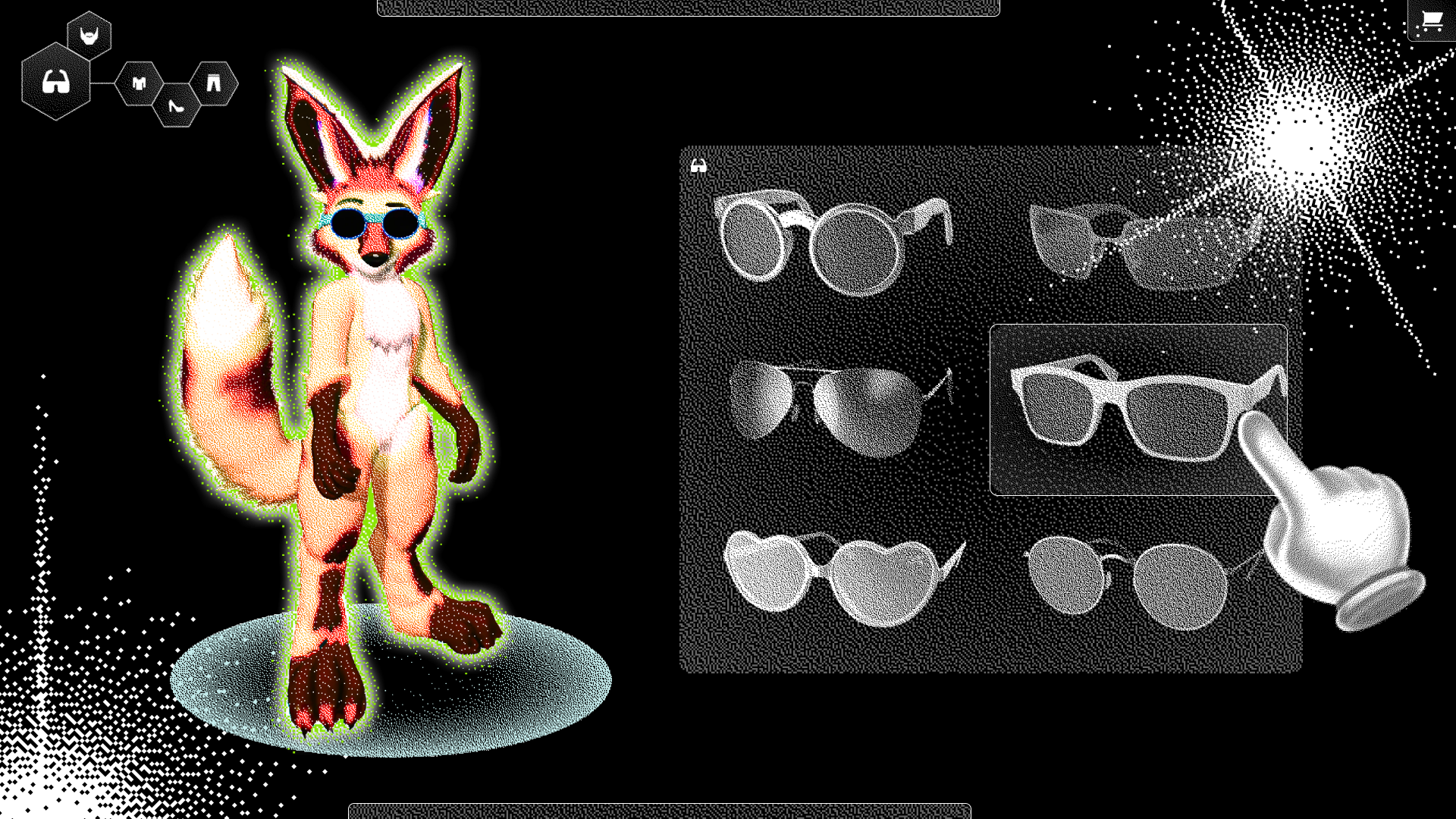

The work, a collaboration with an artist called Skife titled “Right Click Save This,” was an image of Pepe the Frog giving the middle finger, superimposed over an array of cartoon animals. But these weren't ordinary animals: these were fursonas, a kind of digital image used by people in the Furry subculture to express their animal identity. And the work’s sellers had lifted them off the internet, without compensating the people who’d created them.

The piece sold for approximately 20ETH, a little more than $94,000 USD at the time. The creators of the fursonas didn't make a dime off the transaction, a fact that the work itself seemed to rub in with a rotating series of captions: "LAWSUIT MATERIAL." "CALL: 1800-SUE-ME.”

The backlash from the furry community was swift and furious. Folks who found their creations included in the image filed DMCA complaints; others took to Twitter to demand that the artwork be taken down from marketplaces. (Per a VICE report, VincentVanDough eventually offered to pay affected creators $5000 for a one-of-one NFT of their fursona, but only if they could “verify” that they were “in fact the creator of the original.”) On forums and social media threads, furries complained about the rampant art theft in the NFT world and its negative impact on creators. They decried the increasing financialization of art that NFTs made possible and exhorted members of the community to refrain from participating in web3, even if they were promised a good return on investment. The incident was just one of a number of clashes between the furries and the crypto community during the bull run of 2021.

As a cyber ethnographer, I found it notable that the two groups were so at odds with one another. Both communities, after all, favor self-identification through images of drawn animals. Both have very particular views about ownership of digital art and digital identity, and engage in a similar set of behaviors: buying and selling unique personal avatars. But the similarities stop there, and the differences reveal a fundamental disagreement about how the world works: the message of Right Click Save This is that people are untrustworthy by nature, and that we need tools to tell us what is authentic and what is not. The furries would counter that we don't need new tools to make transactions more trustworthy; we need people to be more trustworthy.

The system works with little more than unencrypted direct messages and PayPal. It does not need blockchains to function, because the entire ecosystem is bound together by a degree of inter-community trust.

Digital art has been around since the 1960s, and, yet, selling it has always been an issue. Digital goods flipped the whole premise of classical economics by eschewing scarcity altogether — how do we sell a good that is infinitely reproducible? Crypto (and specifically, non-fungible tokens) enabled digital artists to create scarcity around their work while giving rise to a new ecosystem of platforms where they could sell it, with the option of automatically earning a cut on all secondary sales. It also created an infrastructure that allowed fans to build communities around artists and collections. But furries have been selling unique digital art and building communities online for the past 20 years, without needing to outsource the trust to non-human agents in the form of blockchains.

Since 2015, I’ve been a member of a Facebook group called “Furry Art for under 20$.” During that time, I’ve witnessed and been privy to hundreds of exchanges of unique artworks and fursonas. The process is straightforward. Group members looking to purchase a fursona browse the group for an artist they like, then send that artist a message requesting a fursona with specific characteristics. The artist will quote them a price, and once accepted, the purchaser pays the artist upon delivery of the work. Importantly, as the name of the group shows (“under 20$), many creators provide low-cost entry points for people who want to join or acquire artwork, thus making ownership of these digital identities more accessible and inclusive.

The system works with little more than unencrypted direct messages and PayPal. It does not need blockchains to function, because the entire ecosystem is bound together by a degree of intercommunity trust. If someone were to steal somebody else’s fursona and pass it off as their own, they would face anything from a barrage of disapproving messages from community members to public callouts, all the way to expulsion from the group or forum.

Some very valid questions should emerge at this point. How can a buyer be certain that the fursona they are purchasing is unique? How do members ensure the person they bought the artwork from is the true author? How are sales disputes dealt with?

There is no single answer here. The central tenet of this essay is that the solutions a community comes up with to address these pain points will inevitably be driven by that community’s ideology, with technology as a downstream effect. By comparing how both regions of the internet have responded to these issues, we can illuminate the causal relationship between worldview and technology. Pointedly, two worldviews collide here on the issue of trust.

FURRY HISTORY

The furry fandom dates back to the 1970s, when interest in anime grew in the United States alongside other underground fandoms such as Star Wars and Trekkies. The ’70s were a tumultuous time in America. Society became increasingly fractured as debates raged over gay rights, the Vietnam war, eroding public trust in government thanks to the Pentagon Papers and the Watergate scandal, animal rights, runaway inflation, gas shortages, and other contentious issues. As the post-World War II salad days withered, leaving the stable New Deal and Fordist economy in the past, life for many Americans became increasingly economically precarious. Lacking strong social connections at home or work, people began converging around various subcultures.

At first, furfans — another word for members of the furry fandom subculture — began gathering at science-fiction, fantasy, and comic conventions, where they would mainly discuss the latest in anthropomorphic cartoons. In 1977, Mark Merlino and Fred Patten organized what is widely considered to be the first conference dedicated specifically to furfans, the “Cartoon/Fantasy Organization.” The event was held at the Holiday Inn Bristol Plaza in Costa Mesa, California and featured a furry costuming workshop, dealer’s rooms for sellers, an art auction, and a screening of the film Animalympics.

As much as it was an outgrowth of fandom culture, the furries were also a subsection of a larger social movement that, post-Stonewall, pushed LGBTQ people to build chosen families and communities that could provide safe spaces away from oppression.

Before long, furry culture had expanded from conventions to publications like Vootie, an early furry zine that helped popularize the movement. Vootie, which published its first issue in 1976, functioned like an amateur press association: fans would create comics or write essays, and then send them to a central editor who would compile the submissions and publish them. This emphasis on community-based artistic production became an integral part of furry subculture. As Kameron Isaiah Dunn points out in his essay, “Aesthetic Fandom: Furries in the 1970s,” the publication contained references to the Gay Liberation Front and Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation — directly reflecting the social anxieties of the era, along with the sexual identities of community members.

Queerness was, and remains, an important part of the fandom. As much as it was an outgrowth of fandom culture, the furries were also a subsection of a larger social movement that, post-Stonewall, pushed LGBTQ people to build chosen families and communities that could provide safe spaces away from oppression. As Dunn aptly points out, “the furry aesthetic skews towards queer utopic world-building.” And, as time passed, that world-building migrated from the analog world to the internet.

In 1982, Merlino began hosting the first furry-focused electronic bulletin board, a kind of early online community that users could access using a modem and landline, out of his house. This online congregation space, where people would read and exchange messages with other users, foreshadowed the central role that digital communication would play in the community. In 1990, BlueMage, a student and member of the fandom, created a Multi-User Creator Kingdom called FurryMUCK, a kind of early, text-based virtual world where furries could role-play and converse. It remains active to this day.

As Jose Esteban Munoz observes in Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, “Queerness is essentially about the rejection of a here and now and an insistence on potentiality or concrete possibility for another world.” For nearly half a century, the furries have been experimenting with various forms of cultural production, online and offline, that offer us glimpses of what that queer futurity could look like — a world anchored in values of community, inclusion, and acceptance. The market they have built — and the technologies, digital and social, that they have chosen to employ — are a reflection of those priorities.

What kinds of systems would a group of individuals anchored in values of community, inclusion, and acceptance create?

The origins of the fursona are hard to pinpoint. The idea of costumes is inherited from sci-fi and comic conventions, where fans would dress up as their favorite character. As furfans began to convene at furry parties, which were originally adjacent to said conventions, costumes became an increasingly important part of the culture. Furthermore, I hypothesize that as people developed affinities for specific costumes and began wearing them more frequently at gatherings, they began to socially identify with the costume and, ultimately, a persona.

Later, as the fandom moved online, these personas would sometimes carry over to the digital realm. The physical costume became a drawing, which, when digitized, became a fursona. However, the furries fandom differentiates between two types of fursonas: the “personal furry” and the “avatar.” The personal furry is a character the individual holds a strong personal connection with. The avatar is a platform-specific identity, which can be switched as an individual enters other spaces. Because some furries lacked the artistic skill to create their own fursonas, a market emerged where artists created custom digital characters for sale, known as Adoptables.

Over the years, the furry community has cycled through various different platforms for buying and selling digital Fursonas and Adoptables. From 1999 to 2014, the most popular ones were Furbid and Furbuy. Currently, the majority of the sales happen in small Facebook groups, where interactions and trades are self-moderated. Transactions mainly happen through payment services like Paypal as well as The Dealer’s Den. The Dealer’s Den is the only active platform dedicated specifically to selling Adoptables, though one can purchase physical items such as props, fursuits, plushies, and other furry-related paraphernalia there as well.

When you log on to one of these groups and purchase a fursona, there is no blockchain you can reference to verify that its provenance is legit. So how do you know that you’re buying what you think you’re buying? Though practices vary from group to group, the furry community has a number of strategies for ensuring that transactions are honest. Mods of the group expel members who repeatedly contravene community guidelines. To determine who owns which fursuit, the community runs a volunteer-managed fursuit database. Currently, more than 4,400 fursuits are cataloged on the site. Though the database only catalogs physical fursuits, furries on these forums look out for one another and will bring it to a mod's attention if someone is trying to falsely pass off a design as their own.

Because the approach to trades is community-oriented instead of merely transactional, exchanges can be reversible. Take, for instance, one incident where a furry ended up spending over $20,000 on an Adoptable after taking a higher dose of their medication. Had they asked for it, they could have obtained a refund. In this way, the exchange runs on community and trust. It has the flexibility to allow room for human error.

CRYPTO HISTORY

Like Sirin to the furries’ Alkonost, cryptocurrencies operate on an ideology antipodal to that of the furry fandom. Though you can trace the philosophical origins of both movements back to the Cold War era, their markets operate on opposite premises. Whereas the social fragmentation and the stagflation of ’70s America led the furries to build a united community based on trust and long-lasting interpersonal bonds, the 2008 financial crisis confirmed for cypherpunks and crypto-anarchists their complete distrust of institutions — along with the primacy of what they called the “sovereign individual.”

The concept of the sovereign individual was popularized by William Rees-Mogg and James Dale Davidson’s 1997 book by the same name. It’s a favorite of crypto-evangelists like Naval Ravikant, Brian Armstrong, and Peter Thiel, who wrote the preface of the 2020 edition. As Rees-Mogg and Davidson saw it, “Industrial technology gave governments greater instruments of control in the twentieth century than ever before.” As a result, “it seemed inevitable that governments would become so effective at monopolizing violence as to leave little room for individual autonomy.” Accordingly, the book promoted a worldview that emphasized self-ownership, personal freedom, and a distrust of the state.

Unlike communities where the deterrents are social, trustless communities embed the deterrents within their infrastructure, eschewing the difficulty and messiness of human cooperation and its shadow, conflict. This is all well and good until that messiness inevitably comes back to haunt us.

The authors harken directly to the work of Friedrich von Hayek, the British-Austro-Hungarian economist who the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1974 — specifically, to his book The Road to Serfdom, in which he argues that fascism is amenable to central economic planning and increases in state power to the detriment of the individual. For disciples of Hayek and Rees-Mogg, the 2008 crisis represented a catastrophic failure on the part of the government and the financial system, making the idea of carving out an existence outside of these institutions became increasingly desirable. Only now, with technology, it was achievable.

What kind of systems would a group of "self-sovereign" individuals build?

Revisiting the ideas that led to the invention of Bitcoin, cryptocurrencies, and NFTs illuminates the specific technologies and infrastructures the Cypherpunks and crypto-anarchists would end up creating. The concept of a “trustless” system implies a group of lone agents interacting with one another. Because they are sovereign and not interdependent, such systems must be built with game theory incentives to prevent any wrongdoing from the agents. Unlike communities where the deterrents are social, trustless communities embed the deterrents within their infrastructure, eschewing the difficulty and messiness of human cooperation and its shadow, conflict.

This is all well and good until that messiness inevitably comes back to haunt us. If you shell out a thousand dollars for an NFT, then realize you sent it to the wrong wallet address, there is no way to get it back. If someone creates an artwork out of 100 fursonas they lifted off the internet and then sells it on the blockchain, the transaction remains there forever, immutably.

Day after day, we encounter the limits of trustlessness in a world that is still anchored by interpersonal relationships. Trustless systems don’t just create an environment where we have little recourse if something goes wrong; they can lead to increasingly radical behaviors focused less on mending conflict and fostering long-term community growth than on forking protocols and communities over disagreements. Ethereum Classic and Bitcoin Cash are good examples of this urge to fork. This is not a bad thing, per se. Members of a community should be empowered to branch off when they feel an impasse has been reached. But community design should also include paths for reconciliation.

Digital communities based on interdependence tend to build long-lasting bonds and stick together through tribulations. The furries have persevered through digital transformations, scandals, and internal conflicts — and their story is a reminder that most human interactions still require trust. This is especially important when it comes to art, which is a particularly relational practice.

And yet, perhaps there is a path forward, somewhere between the thesis and the antithesis. Which is the question that I beg you to consider: how might we use “trustless” tools to foster in communities a greater degree of trust?

Ruby Justice Thelot is an artist, writer, and cyberethnographer based in NYC. His writing focuses on digital phenomenology, virtual ontology, and the implications of being-on-line. He has given talks and exhibited work in Tallinn, Berlin, and Abuja.

Images by Carlos Sanchez