- Ariel LeBeau

- Austin Robey

- David Blumenstein

- David Ehrlichman

- David Kerr

- Devon Moore

- Dexter Tortoriello

- Drew Coffman

- Drew Millard

- Eileen Isagon Skyers

- FWB Staff

- Greg Bresnitz

- Greta Rainbow

- Ian Rogers

- Jessica Klein

- Jose Mejia

- Kelani Nichole

- Kelsie Nabben

- Kevin Munger

- Khalila Douze

- Kinjal Shah

- LUKSO

- Lindsay Howard

- Maelstrom

- Marc Moglen

- Marvin Lin

- Mary Carreon

- Matt Newberg

- Mike Pearl

- Mike Sunda (PUSH)

- Moyosore Briggs

- Nicole Froio

- Ruby Justice Thelot

- Simon Hudson

- Steph Alinsug

- The Blockchain Socialist

- Willa Köerner

- Yana Sosnovskaya

- Yancey Strickler

- iz

Thu Jun 23 2022

Mindy Seu’s Cyberfeminism Index is a project with a simple aim: to create an archive of as many cyberfeminist resources and references as possible. It’s also wildly ambitious: Seu says the term, coined in 1991 by the philosopher Sadie Plant and the artist collective VNS Matrix, has evolved in multiple directions since its origins in early web history, when it prompted women and marginalized communities to imagine what a different kind of cyberspace might look like. Cyberfeminism began as a critique of an internet that was being shaped in the image of the male gaze, going beyond sci-fi femme-bots to make room for new forms of online identity. Over the past three decades, the movement has evolved to make room for conversations about race, politics, and gender fluidity; it certainly can’t be reduced to just “women,” “technology,” or “feminism.”

Seu, a designer and researcher, launched the index in 2019 with an open call and an open-access spreadsheet, archiving hundreds of manifestos, critical essays, art works, histories, gender studies, and other initiatives. Now a richly descriptive (yet aesthetically pared-down) website, the Cyberfeminism Index pulls viewers into a different version of internet history, filled with cyborg witches, otherworldly utopian fantasies, and slime. And though it kicks off with a seminal text by Donna Haraway, it makes a point of telling that story from the perspective of lesser-known thinkers and makers, like bio-hacker Mary Maggic and the xenofeminist collective Laboria Cuboniks.

This fall, the index will be printed for the first time, by Inventory Press. In support of the publication, Seu has curated an online exhibition of formative cyberfeminist works called WETWARE, on Feral File. Shown chronologically, the exhibition strives to open a dialogue between different generations of cyberfeminist artists and thinkers and features editioned works by VNS Matrix, Linda Dement, Prema Murthy, Shu Lea Cheang, Skawennati, Mary Maggic, Cornelia Sollfrank, Morehshin Allahyari, and Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley.

To celebrate the opening of WETWARE, Friends with Benefits’s Head of Brand Lindsay Howard caught up with Mindy Seu for FWB’s NFT Pirate Radio. We’ve reproduced their conversation — which has been edited for length and clarity — below. —Eileen Isagon Skyers

Lindsay Howard: I'm a longtime fan of yours and have been following the development of your Cyberfeminism Index. What made you want to delve into this research?

Mindy Seu: When I was studying at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, I had a fellowship at the Berkman Klein Center for the Internet and Society. There were a lot of brilliant people around me, many of whom were lawyers and policymakers. I came in as one of the few people with an artistic perspective. I noticed that there was an overlap between online radical activism, pedagogy, and net art — and a desire to look at how people are creatively using the internet as a tool. As I compiled references for myself, the project naturally evolved into what it’s become today.

For those who are just catching up on what cyberfeminism is, do you have a brief definition that you like to use?

The term “cyberfeminism'' was coined in 1991, by Sadie Plant and VNS Matrix. “Cyber” came from “cybernetics” in the 1940s and then “cyberspace” in the 1980s, coined by William Gibson in Neuromancer. Cyberspace was characterized by depictions of the male gaze, like femme-bots and cyber-babes. Sadie Plant and VNS Matrix wanted to flip that on its head: How could women and marginalized communities envision cyberspace, techno-utopia or dystopia? This is where they started to use beautiful, provocative language to propose fantastical spaces, world-building, slime theory, and all of this great, oozing technology. Cyberfeminism is about feedback: New technologies are used, but also criticized through their use.

Are there one or two projects that exemplify the ethos of cyberfeminism?

Of course, the most iconic piece would be “A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century,” which was published by VNS Matrix and initially created the space for this conversation. In the piece, they talk about the “big daddy mainframe,” the mercenaries of slime, and how the clitoris is a direct line to the matrix. The piece has been translated into a number of different languages.

I read an op-ed in the New York Times this morning called "The Future Isn't Female Anymore,” and it was talking about how people are pushing back on the word “feminism” because it’s too simplistic and identity-driven. You’re using the same word, but your definition feels different; it’s not the second-wave feminism of the 1970s.

The prefix “cyber” is essential. For the opening of the WETWARE exhibition, we hosted a series of conversations that touched on this topic. Cornelia Sollfrank, one of the early pioneers of net art, talked about how while she was one of the original cyberfeminists, the word stopped working for her over time, and now she prefers to call herself a “techno-feminist.” We’re also seeing the term “glitch feminism,” coined by Legacy Russell, and “xenofeminism,” by Laboria Cuboniks. In my essay on cyberfeminismindex.com, I try to explain how “cyberfeminism” is an imperfect umbrella term, but that it helps us bridge these two worlds and begin to speculate, define, and redefine this emerging space.

You write that feminism and cyberfeminism aren’t just about women’s bodies, but also about marginalized bodies and marginalized groups of people.

It's not specifically for women who use technology. I feel like that would be such a reduction of what the potential is — similar to feminism itself not only being for women, right? It's about trying to examine the structures of patriarchy that affect all of us, regardless of our gender orientation. Of course, there are a lot of racial components in this too if you think about the history of the word “feminism” in the US, which is why Kimberly Crenshaw's intersectional feminism emerged, or even [the term] “womanist.” There are many different proposals for a new term, and I feel like that makes its meaning even richer.

The Cyberfeminism Index has more than 700 entries and goes back three decades. How did you approach organizing all of this information?

Initially, it was structured based on the open-source spreadsheet that Rhizome released online for their Net Art Anthology. In some ways, it’s quite straightforward: Each entry has a title, date, and author. But then we tried to expand it into more nebulous categories, like hackerspaces, open-source software, biotech, machine learning — all of these different subsections of cyberfeminism. My favorite distinction was what Judy Malloy calls “yack and hack.” “Yack” referred to “yacking” — like talking, or theory — whereas “hacking” referred to “making.” The index shows that theory and practice are very much entangled.

The first entry is “Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late 20th Century” by Donna Haraway in 1985, which is probably one of the better-known projects. But then there are a lot of underground gems, too. How did you go about finding your sources, especially the more obscure ones? Did you ping from reference to reference? It seems like that would be a fun process.

I started the project in an academic setting, so I was reading articles and then scraping their bibliographies for more information. Eventually, I started calling people and getting oral histories about their experiences. Again, it was a blend of theory and practice. I had calls with Judy Malloy, Salome Asega, Ruth Catlow from Furtherfield, and Dr. Charlotte Webb, who cofounded Feminist Internet. They were willing to get on the phone with me and share their own projects or other ones I should look into, and then the index grew from there.

In 2020, I received a Rhizome commission to crowdsource more entries. Once I added the “submit” button, people were able to self-identify as cyberfeminists and submit their own and others’ projects. The printed version of the index will be a selection of these works, all cleaned up, with proper citations and cross-references in between them. It’s been a long process. I feel like I've been pregnant for three years. It's such a personal experience, and now I'm preparing for it to live out in the world, which is daunting but exhilarating.

What didn’t make it into the book? Did you have any debates about what would or wouldn’t fall under the umbrella of cyberfeminism?

Yeah, for sure. I tried to focus on the feedback loop. The projects [we included] not only had to use technology; [they] had to comment on or critique it. For example, someone submitted the hashtag #metoo as an entry. I actually felt like it didn't qualify as cyberfeminism, because even though it was using technology to facilitate the movement, it wasn't actually about technology itself. This distinction helped reduce the scope and remove anything that would make the term too muddy. I also experienced some projects I thought were perfect for the index, but the artists reached out to me and said, “Oh, I don’t actually self-identify as a cyberfeminist. Could you please remove my project?”

Where do you see the project going from here? Will it be open source so everyone can contribute, or do you plan to stay on as the editor?

Right now, I’m focused on producing the physical copy of the book, which will end up at around 600 pages. Danielle Wu received 800 image permissions, Laura Coombs designed the book, and then Lily Healey scripted the entire book with Laura's designs. Beyond the book, the website will grow in perpetuity. We're hoping the website will continue to act as a living archive — a very grassroots, communal archive — whereas the book will add some posterity to this project.

Are the majority of these projects accessible online? Where do they live now?

That's a great question. Many of the net art pieces that you see from the ’90s and early ’00s are really hard to find online, so I linked to them on Conifer and Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. Sometimes things are broken or missing, and other times there are emulations or screenshots of the websites. For the academic articles, I would download them from JSTOR and then link to that.

Thank you, Mindy!!!

Yes, we’re pro-piracy!

How would you describe your own relationship with cyberfeminism? Did you discover projects that particularly resonated with you and your practice?

One of the works in the WETWARE show was this really iconic work from the late ’90s called Bindigrl, by Prema Murthy. [At a time when] pornography was proliferating online, Prema was commenting on the racial and gender stereotypes that were and are being exacerbated in these platforms, and how she might be able to reclaim them. So she basically creates an online forum and talks about how Bindi is her avatar in screenal space — this archetype of a Hindu deity that represents the goddess/whore binary and complicates them.

Things like this felt resonant because as active online users, we all have our experiences with trolls, but we also have our experiences with how we can empower ourselves. So I think the cybernetic sexual quality of technology was really exciting to see. [I also wanted to emphasize] the work of my friends and peers. Nahee Kim has this project called Daddy Residency, where she puts out this open call for a daddy, for people to submit proposals for artificial insemination and how they might raise the child together.

How did the artists in the exhibition respond to the idea of entering into crypto and NFTs, since many of them were doing so for the first time?

We hosted a series of Twitter Spaces during the opening, and one of the interviewers, Yana Sosnovskaya, introduced a new-to-me term for describing an artist’s first-ever NFT release: “genesis project.” It turns out that all of our artists, with the exception of Cornelia Sollfrank, released their genesis project for this exhibition. We reached out to some people who were very skeptical and wouldn’t participate because of proof of work and the ecological component, but most were excited to make their pieces more accessible. It felt like a natural translation of cyberfeminism itself: Artists want to play with and use new technologies, even when they’re critical of them, as a way to understand the pros and cons and different breaking points.

I saw some projects last year by early net artists who were coming into the NFT space. They were either selling early, iconic pieces, or adapting the ideas behind them into entirely new works. Do you think it affects an artist’s legacy to suddenly transition into being more commercial, especially since that’s something many early net artists were pushing against?

A lot of the artists were kind of factoring this in when thinking about what they wanted to make saleable or not. Many of these works were exhibited in art galleries, but they were never sold or revealed online as a net art piece; they were just accessible for free online. The artists were also grappling with why they would want to put something online, and I feel like maybe the sweet spot was revealing materials that complemented the original work.

On Feral File, you’re able to have collector’s packages alongside the artwork, featuring interviews, process footage, and archival footage that you otherwise couldn’t find online. We also have people like Skawennati, one of the first indigenous media artists and net artists, who reveals never-before-seen-footage from her machinima [mini-series] TimeTraveller™. She was able to give us the trailer, and the "commercial" for these time-traveling sunglasses for this Mohawk man named Hunter, that have never been seen in a gallery.

What was it like curating an exhibition on Feral File? Can you share some of your favorite works from the show?

It was great, because I had a lot of autonomy and support from Feral File co-creator Casey Reas, who is an artist and one of the developers behind the creative coding software Processing. Cyberfeminism is so expansive and ever-mutating; the show prompted me to narrow in. And as I was thinking about the embodiment and sliminess, the term “WETWARE” seemed to hit the right note. It referred to hardware and software, but focused on the human element.

We have a work from Mary Maggic called Housewives Making Drugs, which is this fake reality TV show about how to make your own hormones. [The works are also] shown in chronological order. So, the first work — The Contested Zone, by VNS Matrix — first appeared in 1993. Then we have Linda Dement's Cyberflesh Girlmonster from 1994, and Prema’s work from 1997. Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley made two music videos for this exhibition that she modeled after diss tracks: “Social Capital Fights” and “Putin's a WASTEMAN.” I appreciate her work, because even if it’s really critical, she incorporates humor to ease the tension and encourage productive disagreement.

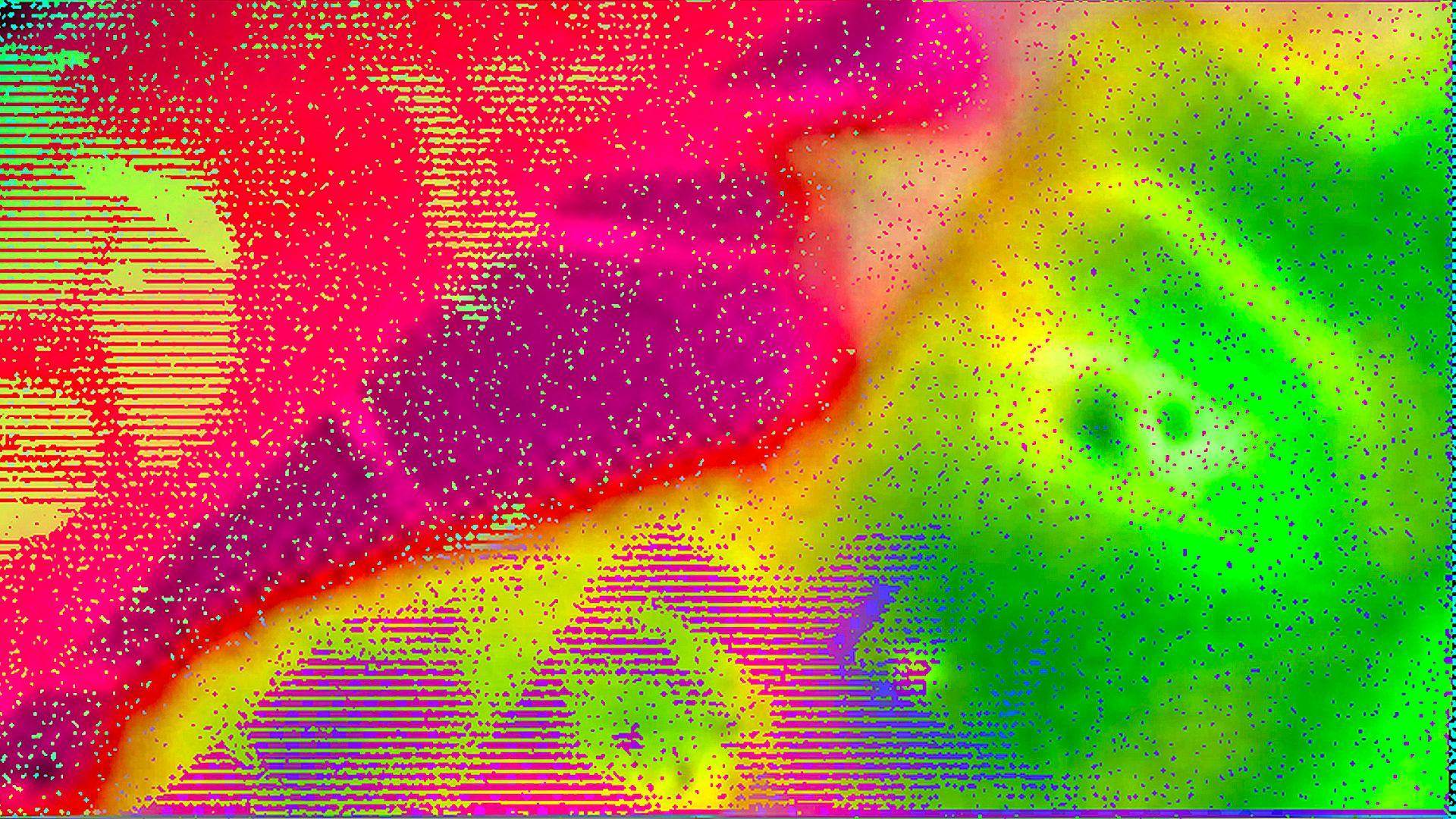

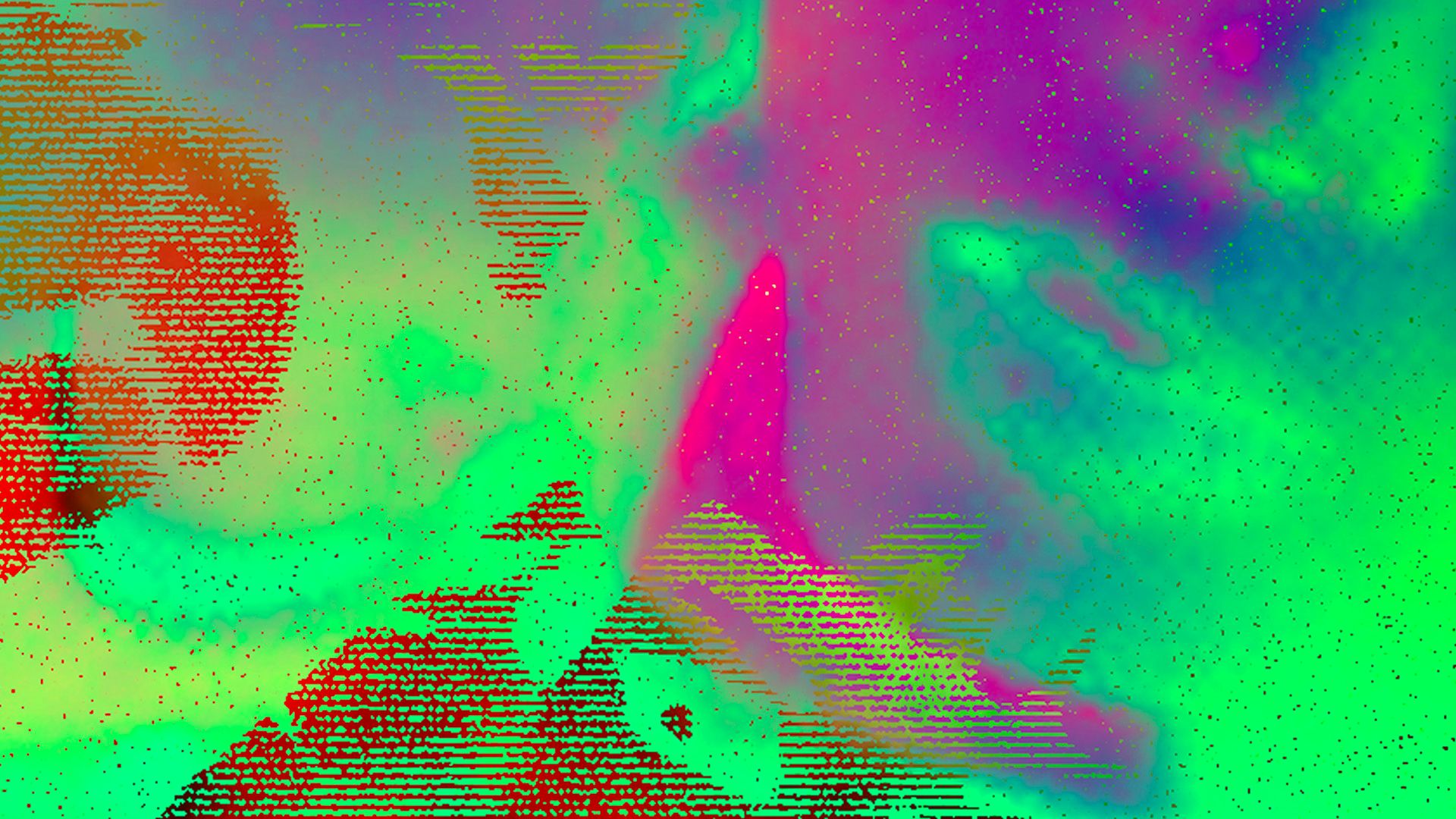

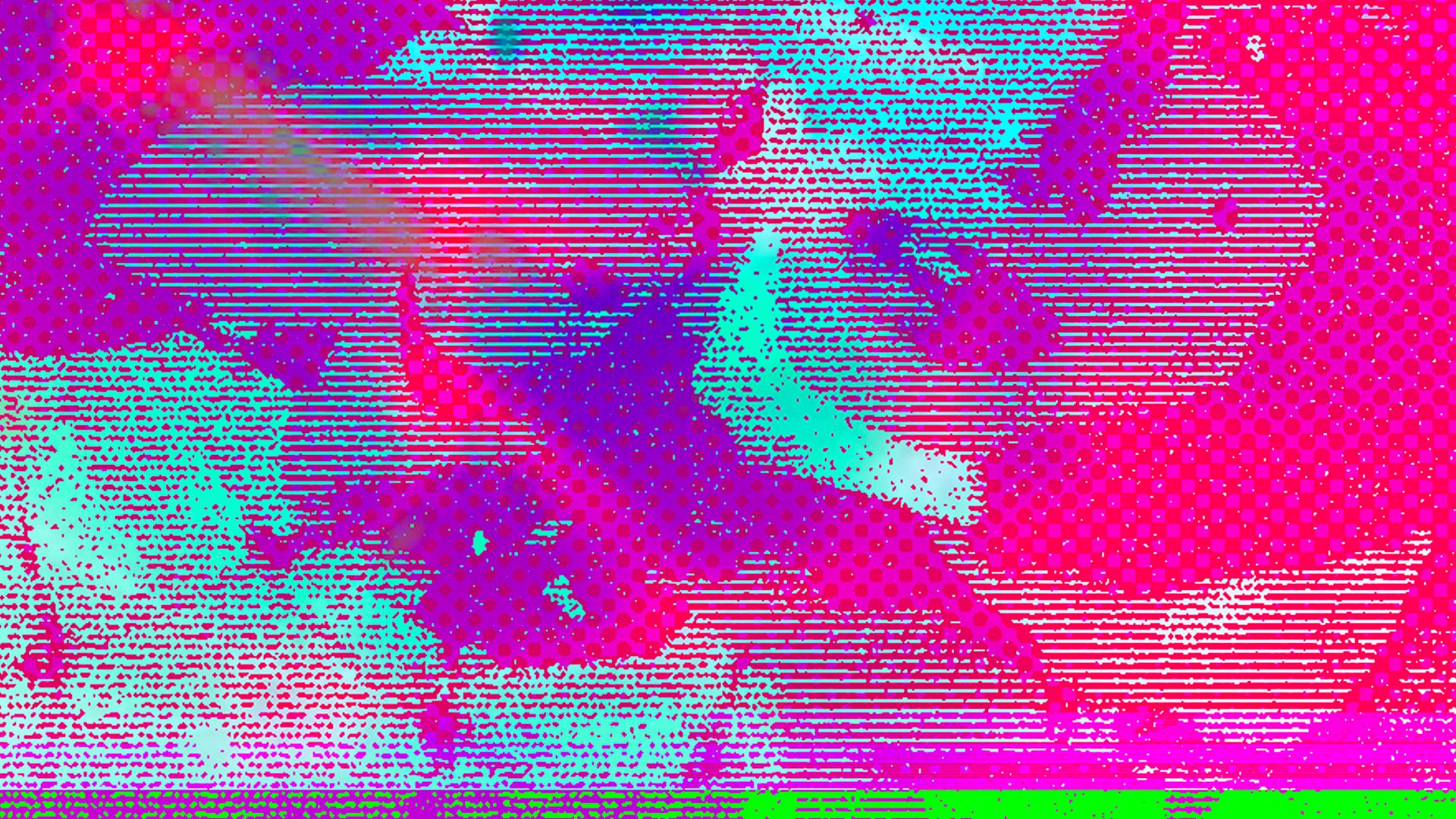

One of my favorite works in the show is by Shu Lea Cheang. She's been one of my favorite artists for a long time, so I was thrilled that she was down to participate. In 2000, she created a [feature-length sci-fi porn film] called IKU, which means “to orgasm” in Japanese. She's recognized for creating a new genre of sci-fi queer cinema. In the film, shapeshifting cyborgs collect “orgasm data.” The character that you see in the cover image for WETWARE is Tokyo Rose, [who is a coder in this futuristic world].

IKU: Expand: an Interface was a supplemental interactive web experience that came out alongside the movie. It’s no longer online, but Shu Lea gave me the source code for Expand, and choreographed how she wanted it to be recorded. So this screen recording has become video art that is available to collect on Feral File.

Andrew Benson just left a comment on Discord, responding to what we were discussing about mixing net art’s history and commerce. He wrote: "I think a lot about how ahistorical the Web3 space feels mostly — almost as if we're starting from scratch, total blank slate, and having to reintroduce the kind of groundwork that early net artists were doing. And then introducing those things also changes them because the context is really different." What do you think about that?

I think these works are all dealing with, in some ways, a form of consent, and mutable contracts: social contracts, social codes, technologies of care, and somehow then translating that into this new space. It definitely feels like there's this dialogue happening, and I'm excited to see that bridge. For me, it feels like there's an opportunity to not only generate new works in this NFT space, but also figure out how to adapt some of these seminal net artworks [in a new context]. There are so many parallels [between all these works], even if they're from different generations.

WETWARE feels different from the ahistorical conditions Andrew describes. It’s powerful because it’s the exact opposite: It’s historic, it’s activist, it’s political. Or, maybe I should pose that as a question to you: Do you see this as being a political project?

In many ways, yes. We're trying to re-introduce these works into the world, and to do so in a way that is critical of and in response to the socio-political landscape in which they were released. It's proudly critical, historical, and contemporary.

Lindsay Howard is the Head of Brand at FWB. A distinguished curator and expert in contemporary art, Lindsay has spent the last decade organizing projects with the New Museum, Museum of the Moving Image, Kickstarter, Eyebeam Art and Technology Center, and Phillips Auction House. She has written and spoken extensively about digital art and new approaches to valuation. In 2021, Fortune recognized her as one of the top 50 influencers in the NFT space.

Images from Shu Lea Cheang ‘s IKU: Expand, an interface, remixed by Chuck Anderson.