- Ariel LeBeau

- Austin Robey

- David Blumenstein

- David Ehrlichman

- David Kerr

- Devon Moore

- Dexter Tortoriello

- Drew Coffman

- Drew Millard

- Eileen Isagon Skyers

- FWB Staff

- Greg Bresnitz

- Greta Rainbow

- Ian Rogers

- Jessica Klein

- Jose Mejia

- Kelani Nichole

- Kelsie Nabben

- Kevin Munger

- Khalila Douze

- Kinjal Shah

- LUKSO

- Lindsay Howard

- Maelstrom

- Marc Moglen

- Marvin Lin

- Mary Carreon

- Matt Newberg

- Mike Pearl

- Mike Sunda (PUSH)

- Moyosore Briggs

- Nicole Froio

- Ruby Justice Thelot

- Simon Hudson

- Steph Alinsug

- The Blockchain Socialist

- Willa Köerner

- Yana Sosnovskaya

- Yancey Strickler

- iz

Thu Mar 24 2022

Editor’s note: Though the National Institute on Drug Abuse prefers the term “substance use disorder” or SUD, this piece uses the word “alcoholic” in certain contexts when quoting the specific terminology used by AA and its members.

In 1941, a glowing feature in the Saturday Evening Post thrust Alcoholics Anonymous into the American consciousness. The Post article described the organization as “a band of ex-problem drinkers who make an avocation of helping other alcoholics to beat the liquor habit.” Bill Wilson, AA’s co-founder and de facto leader, received thousands of letters from people around the country wanting to start their own meetings. He responded personally to each, sharing what other members of AA had learned from their attempts at starting and governing their own groups.

He explained that groups were self-supporting: They would buy the coffee and pay the rent for meeting spaces from a shared bank account. They would vote on initiatives to pursue, elect people to service positions to run the meeting or set up the room, and, importantly, kept a narrow focus on helping people with drinking problems.

Up to that point, the network had grown very slowly, mostly by word of mouth and mainly around a few cities and towns east of the Mississippi. When the first meetings started in 1935, Bill only needed to drive between AA’s main centers in New York and Ohio to share and comment on group challenges and help foster a sense of shared values. But with the letters streaming in, Bill knew he could not keep up as the main conduit of the community’s experiences and wisdom. He faced the dilemma of needing to scale Alcoholics Anonymous as a united community without creating a bureaucracy that would kill its spirit.

Bill had derived AA’s 12 Steps from a six-step procedure practiced by the Oxford Group, the non-denominational evangelical fellowship where he was able to quit drinking for good. Bill would bring people struggling with alcohol use to the Oxford Group meetings, even though the Oxford Group wasn’t specifically for substance issues — its focus was more general, applying Christian principles to life’s problems. The Oxford Group was also very dogmatic: There was a right way and a wrong way to follow the steps. Bill would later write in the AA history book, AA Comes of Age, “We found that certain of their ideas and attitudes simply could not be sold to alcoholics. [The Oxford Group] was too authoritarian for them.” That resistance to authority, Bill felt, made it necessary for his faction to split off. This fork in the road was the beginning of an organization suited for its particular type of community member, and which opposed any sort of centralized control.

This now-autonomous faction, which was still nameless, was free to determine how to pursue its mission of helping people with drinking problems while building an organization of equals who could get along. From this freedom came many failed experiments. In the first decade or so of AA’s existence, some groups created long lists of membership rules; others tried to start for-profit clinics and clubs or to promote one religious doctrine over another. “It took us a long, long time to become really democratic,” Bill writes in AA Comes of Age. “There used to be so many membership rules out among the groups that if they were all enforced at once nobody—actually nobody—could have joined Alcoholics Anonymous.” Frequently, these attempts at community governance led to bureaucracy that members began to experience as its own oppressive authority — one of the factors that caused the split from the Oxford Group in the first place. In his writings, Bill explains that this led to painful challenges that at points resulted in relapses and some groups collapsing.

When responding to the thousands of letters arriving at his desk in 1941, Bill found himself giving the same answers over and over based on what the surviving groups and members had come to learn in the first couple years of trial and error, lessons that would eventually appear in the preamble heard at the beginning of almost any AA meeting today:

“The only requirement for membership is a desire to stop drinking. There are no dues or fees for A.A. membership; we are self-supporting through our own contributions. A.A. is not allied with any sect, denomination, politics, organization or institution; does not wish to engage in any controversy, neither endorses nor opposes any causes. Our primary purpose is to stay sober and help other alcoholics to achieve sobriety.”

The next five years saw rapid growth for AA. Groups sprung up across the US, with some following Bill’s advice and others not, inadvertently serving as a massive experiment with approaches. In 1946, Bill used the resulting successes and failures as the basis of the 12 Traditions, a set of principles that had proven most effective in fostering community unity and harmony among members. Along with AA’s 12 Concepts for World Service, which established guidelines for the organization’s governance structure, these practices formed the foundation for what is arguably one of the world’s largest and longest running DAOs — an 86-year old decentralized organization bringing together thousands of autonomous groups, with over two million members worldwide.

They are united by a common set of principles — the Steps, the Traditions, and the Concepts — a protocol that they agree works for them. For any DAO doing the hard work of building an organization governed by its community, the story of AA’s evolution has loads to offer when it comes to building enduring consensus that reflects collective needs and wisdom.

Unenforced Rules

The 12 Traditions are a social contract. They aren’t laws that can be enforced, but rather a synthesized report of what worked and what didn’t during that crucial early period. Most of them can be summed up as suggestions for how to avoid individual egos clashing and distracting from AA’s unity around its mission. Tradition One states that members’ “common welfare should come first” and emphasized group unity. Tradition Two enshrines the tenet that no single member of AA can have authority over any other, and that the only authority should be an “informed group conscience.” Tradition Three drives home the group's singular focus: “Our only requirement for membership is the desire to stop drinking.”

Throughout the list is what Tradition Four describes as “the right to be wrong,” meaning there is no one right way of doing things. Even the Steps themselves are presented only as “suggestions,” based on the experience of what has worked for others in AA. “If […] they found something better than AA, or if they were able to improve on our methods, then in all probability we would adopt what they discovered for general use everywhere,” Bill writes in AA Comes of Age.

The right to be wrong recognizes how the strength of the community, of any community, comes from uncompelled consensus — it is not something that can be dictated from the top down. This openness is a powerful ingredient in allowing collective wisdom to emerge, because it allows answers to be found in the minority as well as the majority.

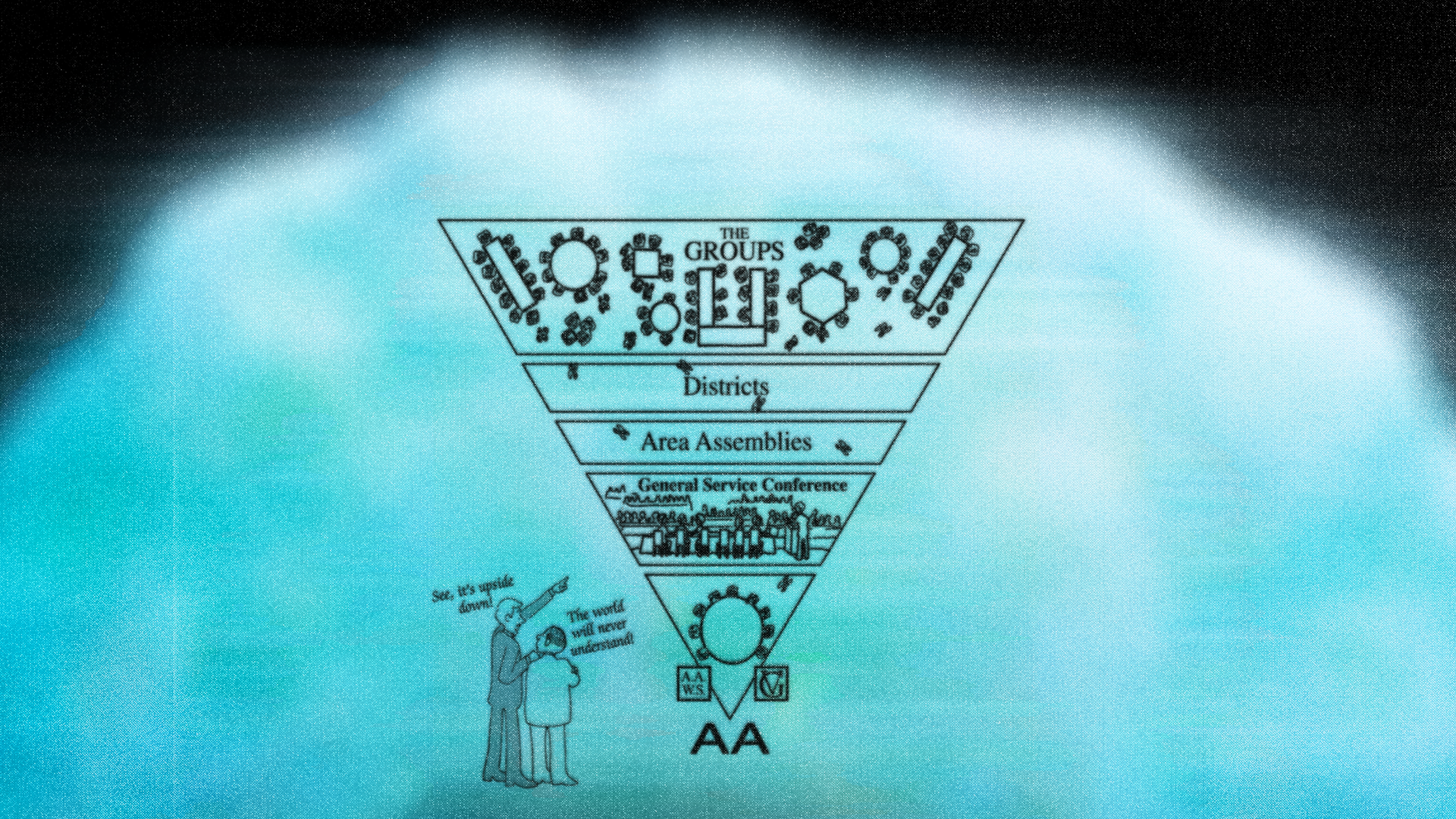

An Inverted Hierarchy

If the 12 Traditions are AA’s social contract, the 12 Concepts are its constitution. Published in 1962, they summed up what the wider community had learned during its first trials of self-governance with the Traditions , establishing a governance structure that took the form of an inverted hierarchy. The individual AA groups are at the top of that hierarchy, with final authority on the decisions affecting AA as a whole. The groups’ needs, questions, and decisions are passed down through representatives in districts, then areas, then to a final annual meeting where delegates and trustees who run AA’s central services vote on decisions around budgeting, updates to the literature, and adapting the organization to the changing times while remaining in sync with the Traditions.

Each successive level of the organization serves the one above it, making the leaders “trusted servants,” in AA parlance, of the wider community they represent. Like the chairperson at the group level who runs the business meeting, hears proposals, and calls the votes, their role is to facilitate rather than govern, helping the groups’ collective conscience come out and guide decision-making.

As anyone working to build a community-governed organization can tell you,there is an inherent challenge with this structure: The decision-making authority is held by people who are disconnected from the actual functions of the core team, including the annual conference where delegates need to process all the information and decide how to vote. So how can groups exercise final authority when they’re not even there when voting happens?

To uphold the ultimate role of an “informed group conscience” in decision making, the Concepts emphasize consensus building. It can take a long time, sometimes multiple annual meetings, to ensure that delegates and trustees have all the information they need from groups. Often a proposal won’t go to a vote until it’s clear it will reach at least a two-thirds majority, so that delegates can be fairly confident that the decision they are making, as well as the details of its implementation, represents the general overall group conscience.

To further ensure that decisions represent the will of the AA community as a whole, the Concepts also establish three Rights: that of Decision, Participation, and Appeal.

The Right of Decision

When someone is picked to be a delegate or hold some other role of responsibility, they are expected to make the best decision possible in the moment. Crucially, the Right of Decision is the right to decide differently at the annual meeting than directed by the groups in their geographical area if they get new information that is relevant to a decision.

This makes the role of an elected leader that of a listener: Though they come armed with an understanding of their community’s concerns and needs, they are there to develop solutions and vote for the good of AA as a whole in the light of all the information available.

The Right of Participation

The Right of Participation is AA’s effort to ensure that just as there are no second-class members, there are no second-class workers under the employ of AA itself. AA’s central offices necessarily employ some non-AA members who have the expertise to run various support services, including print publishing, maintaining the group’s website, and caring for its archives. As a safeguard against the dominating tendency of authority in the workplace, these employees are given voting rights at the annual conference so that the experiences of those with direct knowledge of AA’s operations can be reflected in any decision making. (The exception is when an employee’s own performance is under review, but even then, they are included in the discussion.

The Right of Appeal

The Right of Appeal protects minority opinion against an uninformed, misinformed, hasty, or angry majority. It provides that the minority will always have a chance to make its case after losing a vote. Reports of past annual meetings show that the practice of hearing the minority opinion has at times had the effect of completely reversing votes, as it can help expose critical pieces of information or a dominating bias. Even when an appeal doesn’t change a vote, the ritual serves the purpose of enabling the organization to move forward in full awareness of the pros and cons, and provides those carrying out the decision a caution of the risks involved.

It is important to note that the “right to be wrong” doesn’t necessarily extend to AA’s elected leaders, and that the groups have great freedom to remove anyone they deem is not acting in the best interest of AA. There are also practices like the “spirit of rotation,” which encourages leaders to regularly rotate out of their roles. This helps ensure that leadership always represents the group’s conscience while creating space for more members to understand what it takes to run a decentralized community.

AA as Public Good Protocol

What AA has become over time is simultaneously a single organization and a network of over 120,000 autonomous groups — a DAO with thousands of sub-DAOs. No one is compelled to participate in the structure, and members can essentially run their own group however they like, leading some to call AA a “benign anarchy.” Yet AA still functions with a common language and set of practices. Travel from city to city, and you’ll find the way each group runs is familiar, shifting only in ways that reflect a local flavor.

In a way, AA offers an example of what a public good protocol could look like, even if it’s governed with a social contract instead of smart contracts. A public good is non-excludable and non-rivalrous; it’s an infrastructure that anyone and everyone can benefit from and build upon. Keeping with the tradition of no central authority, anyone can set up a meeting using AA’s protocol of the 12 Traditions and associated knowledge. As a rule, no one can be kicked out of AA, and attending a meeting doesn’t exclude someone else’s ability to.

Over the decades, AA’s central services and governance structure have come to replace what Bill did. Together, they function as a kind of communications network, passing along the experiences of individuals across the organization’s membership and representing the voice and conscience of the entire community. Like a ledger, the central services record and publish the different ways people have made use of the protocol, and these publications are approved at the annual meeting. In addition to AA’s archive of historical experience, all of its bylaws, structures, and organizing principles are available as free PDFs on its website, including The AA Service Manual + Twelve Concepts for World Service and Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions.

At the start of the pandemic, the service structure kicked into high gear to share how groups were learning to meet online. AA as a whole didn’t declare any particular stance on questions like whether meeting with one’s camera turned on violated the tradition of anonymity; it simply shared different groups’ interpretations and their results.

The inverted hierarchy, meanwhile, ensures that every member is a custodian of this public good. The governance structure makes sure the work of the central services is done in accordance with the Traditions and the conscience of the groups, and that any changes made to the protocol reflect overwhelming consensus. Staying true to its nature as a public good, AA has also allowed for forks of its protocol, leading to a plethora of 12-Step organizations covering issues other than alcohol.

Democracy as Therapy

Many DAOs will not be here for long. They will scale much faster than they are able to clearly define what they are essentially about, let alone effectively build consensus as community-run organizations. Frayed focus can lead to deflation of interest or internal conflict. This can cause a group to implode, or make it vulnerable to competition from more compelling communities.

There was a near-identical society that emerged 100 years before AA called the Washingtonians. They too found success using an approach where people worked together to deal with their drinking problems. In the span of four years, the group reached over 100,000 members — the same amount of time it took AA to reach its first 100.

But after just seven years, the organization collapsed. The main reason for its demise was that it had lost its focus on its community. After finding success with solving drinking problems, the Washingtonians tried to apply their methods to any problem that people came to them with, even ones unrelated to substance use. The organization became embroiled in political controversies, taking stances on the temperance movement and abolition, while simultaneously expanding its central authority to more parts of its members’ lives. This led to infighting and a loss of unity.

In the end, AA’s initial slow growth may have saved it. It took over ten years of trial and error to learn what worked before Bill formulated the Traditions, another five for those Traditions to win acceptance by the community, and yet another five years of practice with them before Bill finally handed over the keys to the groups. And that was before AA had even established the 12 Concepts, which required another seven years of experimentation. All in all, it took 27 years for the organization’s governance structure to fully come into place. That may seem like multiple lifetimes in Web3 years, but it’s a stark reminder of the patience that it takes to build a community that is actually built to last.

According to Not-God, the definitive independent history of AA, Father Ed Dowling, Bill’s spiritual advisor, once said that “A.A. has proved that democracy is therapy.” We are seeing thousands of experiments in community governance bloom as DAOs; to be sure, many will fail, or revert to centralized, authoritarian organizations. But the ones that endure will likely be the communities where individuals willingly set aside their self-centered ideas for the good of the group, and take ownership of their responsibility to the common purpose. They will have realized their own version of the democratic ideal Dowling saw in AA: Being part of an organization that takes its direction, not from the limited perspectives of one individual or a cacophony of divergent voices, but from the boundless knowledge and wisdom embedded in the “group conscience.”

The brief excerpts from Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc. (“A.A.W.S.”) and the A.A. Grapevine, Inc. copyrighted material are reprinted with permission. Permission to reprint these excerpts does not mean that A.A.W.S. or the Grapevine has reviewed or approved the contents of this publication, or that it necessarily agrees with the views expressed herein.

A.A.W.S. has not approved, endorsed, or reviewed this website, nor is it affiliated with it, and the ability to link to aa.org does not imply otherwise.

Graphics by Fiona Carty.